Author, Teacher, Wanderer

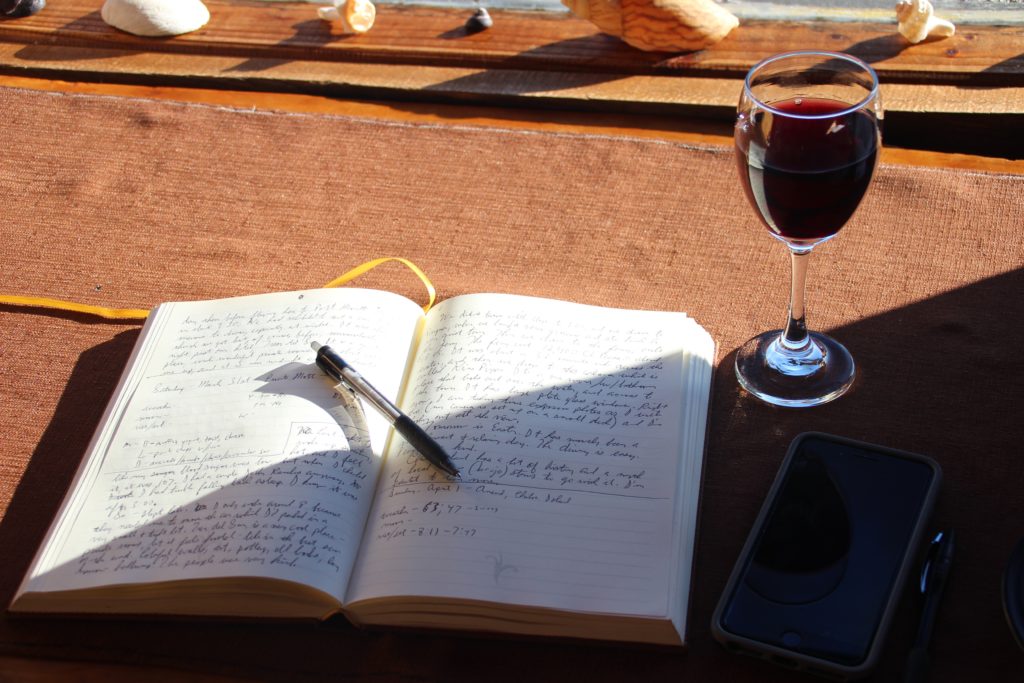

On Journeys and Journals

Tomorrow, my wife Joan and I will begin a slow drive south, to Anchorage and then the Kenai. Homer is the destination, though not really the point. I often create this way. In motion, my mind clears, and, as in sunlight after a storm, worlds both fictional and real reappear. At every stop, I pull my journal, or sometimes my laptop, from my bag and I write. On the drive, in between writing sessions, the stories have room to develop. Last year, as we travelled through Washington and Oregon, I worked on a story about an ex- quarterback. I finished the story, finally, in a brewpub in Astoria.

It seems to me that there is a natural relationship between travel and writing, and, though I don’t know the etymology, it makes sense to me that the terms “journey” and “journal” sound so similar.

I first started writing in journals consistently during the summer of 1985 when I rode my bicycle 5000

miles through the western United States. I rode through a mountain snowstorm and across the 100 degree desert. Along the way I met a Hollywood stuntman who was mending a broken marriage by traveling through Montana, an elderly couple named Dick and Winifred who fed me a meal of freshly harvested clams and oysters and told me stories of life lived near the sea. In Arizona, a Navajo man told me the names of nearby rock formations, and narrated the legends contained within them. I learned the joy of sleeping to the sound of rain against my tent and ocean waves lapping on the shore. I felt various velocities of wind against my skin.

Every day on that trip, I kept a journal. The writing in those old journals is bland, less than literary,

lacking in description and dialogue. But I still have them, and always will. I wrote daily not with the goal of publication, or even with a potential reader in mind, but to keep a record, to remember and to connect with the natural world, connect with my own experiences. To write of one’s journey is to live it twice and because of those journals, that journey remains vivid in my mind, even 28 years later.

Every semester, early — I’m partial to doing this on rainy days– I ask my students this: so what did you notice when you came to class today? They shrug, look around at each other. Was there an assignment they’d missed? Forgotten to do. They glance down at their notes. Then I ask if they noticed the reflection of the leaves in the water, the way they create abstract streaks of red and orange in the puddle outside the building; the man outside collecting cans with the shirt that says “Math is Infinite.” The

swoosh of traffic, how if you close your eyes at a street corner, you can tell when the lights change, just by the sound of those tires coming to a stop. I tell them about the conversation I overheard at the coffee house that morning. Writers, above all else, I tell them, pay attention, notice what others miss. Motion is

central to this. Even if only a daily walk.

My love for books mirrors my love for travel. The travel writer Bruce Chatwin, writes that the nomadic life is the most natural human instinct. It’s no coincidence that many of the best novelists are also travel writers: Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Pam Houston, Jim Harrison, Jamaica Kincaid, Paul Theroux. The travel narrative is one of the most enduring forms in all of literature–from “The Odyssey” to “Canterbury Tales” to Dante‘s “Inferno.” Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” is, in part, a

travel narrative, as is Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road.”

Writing, like bicycling, is best when the destination falls away, and all that matters is the moment. The ego drops away, and a connection is felt, and you enter that effortless dreamlike state, and the awareness is so profound that you are no longer peeking into the world, but have disappeared and folded into it. It’s a lesson I have to keep re-teaching myself: you write a book the same way you bicycle 5000 miles. Steady progress. Not a binge once in a while, but a little every day. On a bicycle tour, you don’t take weeks off. When it rains, you don’t stay inside–getting wet is the point. You don’t quit when

there’s a head wind–you pedal. The wind changes, the clouds clear. Writing is the same. You have to plow through the hardships. Good writing does not come about from brief moments of inspiration

any more than good health does. It requires routine.

And in routine, you discover that journals and journeys have something else in common: a natural arc. By writing every day, you begin to see the escalating and falling actions of life–the obstacles, conflicts, resolutions, joy.

Our lives are our journeys. Let us write them as we go.